"I wanted to be the last woman on earth to have undergone FGM."

Survivors in Kenya say the practice must stop with their daughters

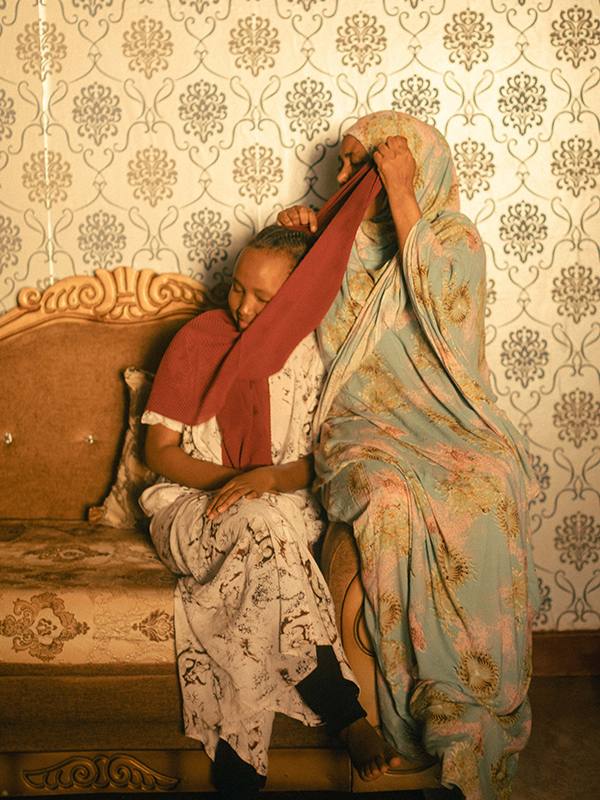

More than 200 million girls and women today are survivors of female genital mutilation. Mumina Jirmo, 34, of Isiolo County, Kenya, is one of them.

“I was seven years old when I went through the cut. I have been through the most painful ordeals, including losing two babies during childbirth. I wanted to be the last woman on earth to have undergone FGM.”

– Mumina

Just like any other girl

Female genital mutilation – FGM – is a human rights violation. The procedure involves partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injuries to the female genital organs for no medical reason.

“It was seen as a cultural norm that we had to go through,” says Mumina. “For me, I saw the need to be just like any other girl.”

Like the millions of other women and girls who have been subjected to the harmful practice, the pain Mumina has suffered is both physical and psychological.

“I experienced pain throughout adolescence, and prolonged labour and postpartum hemorrhage with my pregnancies,” she says. “But the loss of my children was the most painful ordeal. So many women, young mothers, are also going through what I experienced.”

Women Rising

Daughters of survivors face a significantly higher risk of undergoing female genital mutilation than daughters of women who have not undergone the practice. But not Mumina’s girls.

Mumina has established a community initiative – Women Rising – which includes a forum for mothers who have endured the harmful practice and their daughters, who, as a result of community engagement and changing attitudes, will be spared.

Female genital mutilation has been illegal in Kenya since 2011. While it’s vital that the practice is banned, women-led and survivor-led movements such as Women Rising are key to advancing real change.

Survivors have an in-depth understanding of the issues affecting women and girls, and their advocacy and influence are contributing to steadily declining numbers. In Kenya, incidences have fallen over the years, but the rate is still too high, with an estimated 15 per cent of girls continuing to be subjected to the harmful practice; 75 percent of girls undergo the procedure by age 14.

This is the generation that can end it

Bernadette Loloju, 49, is the chief executive of Kenya’s Anti-FGM Board, a state agency created to spearhead initiatives to end the practice. Like Mumina, she would like to see the number of incidences in Kenya fall to zero.

Bernadette is a survivor herself – when she was 13, she endured the procedure at the hands of a retired nurse at her family home. Around the world, 1 in 4 survivors have been subjected to the practice by a health worker, an indication of how widely accepted it has been. But things are changing.

Bernadette believes it is possible to eradicate the harmful practice by 2030, as long as communities are fully engaged in the process. Today, girls are one third less likely to be subjected to the procedure than they were three decades ago; however, progress needs to be at least 10 times faster to meet Bernadette’s goal of eradication by 2030 – which is also the global target.

For Mumina and Bernadette and so many others, their pain and suffering has transformed into defiance and strength. They are not only survivors, but role models and changemakers.

UNFPA will continue to invest in survivor-led movements until every girl is free from this harmful practice.