News

When health workers harm: the medicalization of female genital mutilation in Egypt

- 02 October 2019

News

CAIRO, Egypt – Female genital mutilation has been outlawed in Egypt for more than a decade, but it remains widespread. Yet rather than helping to eliminate the practice, public campaigns highlighting its dangers may have had an unexpected side effect: pushing the procedure from the home to the very place where staff are meant to “do no harm” – the health facility.

“About 75 per cent of female genital mutilation in the country is performed by doctors,” said Dr. Ayman Sadek, an expert on the subject.

Despite years of efforts by the government and health organizations, female genital mutilation remains deeply entrenched in both Egypt’s Muslim and Christian communities. Around 9 in 10 Egyptian women have been subjected to the practice, according to 2015 data.

It was once largely performed by traditional birth attendants known as ‘dayas’, but since the ban, families have increasingly turned to trained health professionals.

The medicalization of female genital mutilation is alarming to health and human rights experts, as it offers the appearance of legitimacy to a practice with no medical benefits but plenty of serious consequences, including possible haemorrhage, childbirth complications and even death.

Some health providers perform female genital mutilation because they believe families will resort to the practice no matter what.

"They say that there's little that can be done to stop this practice, so they agree to do it, but with reduced risk of infection and bleeding,” said Dr. Wafaa Benjamin Basta, an Egyptian gynaecologist. “They to claim lower pain and trauma by doing a little cut under anaesthesia. It's a harm-reduction approach."

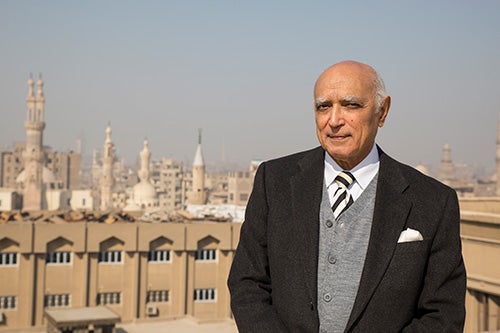

But this is no excuse, said Dr. Gamal Serour, an obstetrician/gynaecologist and Director of the International Islamic Centre at Al Azhar University. “Medicalized female genital mutilation is harmful and unethical,” he said.

And medicalization does not guarantee harm reduction.

In Egypt, clitoridectomy and excision are most common forms of female genital mutilation. Both involve the removal of significant parts of the female anatomy.

Furthermore, Dr. Sadek noted, “when doctors get their training, they don’t learn how to perform female genital mutilation. Instead, they learn it from the traditional practitioners.” Other health staff don’t learn the procedure from anyone, making it up as they go.

There is also another incentive, Dr. Sadek noted: Some perform female genital mutilation to supplement their incomes.

“When you make something illegal, it increases the price,” he said. “I know of one doctor who does the practice on girls but protects his own daughters from being subjected to it.”

Campaigners’ focus on the physical harms caused by female genital mutilation means the psychological consequences have been largely overlooked, some experts said.

"We tend to talk only about the medical impact of female genital mutilation, when the social and psychological impact are just as, if not more, important," Dr. Basta told UNFPA. "I have patients who tell me that it has interfered with their ability to have an enjoyable sex life.”

The practice also arises out of – and reinforces – gender inequalities. It perpetuates, for instance, the idea that women’s bodies are inferior when intact and the idea that women’s sexuality must be controlled.

A 2014 household survey showed that more than half of respondents believed men prefer women who have been cut, and more than 40 per cent said the practice prevents adultery.

Support for the practice remains high even though 60 per cent of female survey respondents acknowledged that it can cause complications resulting in death. Less than half of men were aware of such complications.

But there has been progress, experts say. Recent increases in the penalties for performing female genital mutilation have contributed to an overall decrease in the practice, Dr. Serour said.

And attitudes are slowly changing, particularly in affluent and urban communities.

“Ten years ago, most of my patients had been subjected to it,” Dr. Basta said, noting that among her own clientele, “only about 10 per cent of my patients on the private sector – particularly women under 30 – have had it done to them.”

UNFPA has worked with the department that oversees licensing for private clinics to discourage the practice. And a UNFPA-supported medical curriculum on the harms of the practice has been approved, but not yet rolled out to universities.

Through the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme to Eliminate FGM, communities are also educated about the harms caused by the practice and encouraged to abandon it.

Still, many people remain convinced that medicalized female genital mutilation is acceptable.

“Medicalized female genital mutilation is wrapping a terrible thing in a beautiful package,” Dr. Sadek says.