When school holidays mean FGM

10 Aug 2017

For some girls, school holidays are not all fun and sunshine.

In countries like Guinea, Nigeria and Somalia, the vacation period could be called "cutting season," when the break from school means girls have time to undergo, and recover from, female genital mutilation (FGM).

© UNFPA/Georgina Goodwin

“This is the peak season, when parents bring their children to be cut,” said Asha Ali Ibrahim.

In her community in Somalia, she is a circumciser, a role she inherited from her mother. She supports her family with income from the practice, and is considered the keeper of a cultural tradition. “Circumcision is important as a transition to adulthood," she said.

© UNFPA/Georgina Goodwin

Most of the girls she cuts are from her neighbourhood or the nearby displacement camp.

They are usually 7 to 10 years old. But she sometimes cuts girls visiting Somalia from abroad, who tend to be a little older. “It is a bit cumbersome to carry out the procedure on tissue that is more mature,” she said.

© UNFPA/Georgina Goodwin

The most common type of FGM in Somalia involves cutting the genitals, then sewing them closed.

This practice can cause significant and long-lasting medical problems, including haemorrhage, infection, complications in childbirth and even death

© UNFPA/Georgina Goodwin

Ms. Ibrahim is clear-eyed about some of the dangers. She has taken girls to hospital when they bled excessively.

When her own daughter was cut seven years ago, the girl developed an infection and has never fully recovered.

© UNFPA/Georgina Goodwin

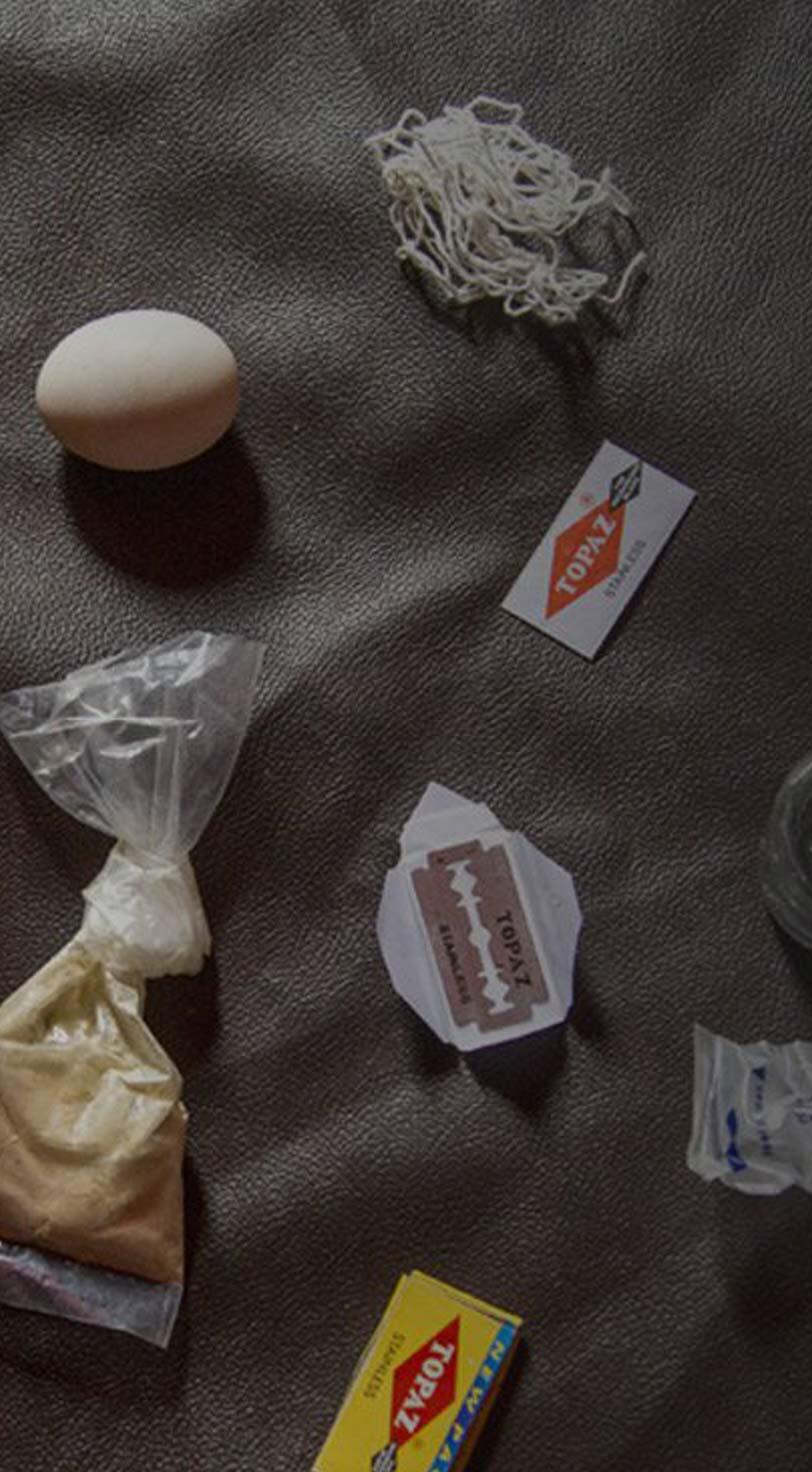

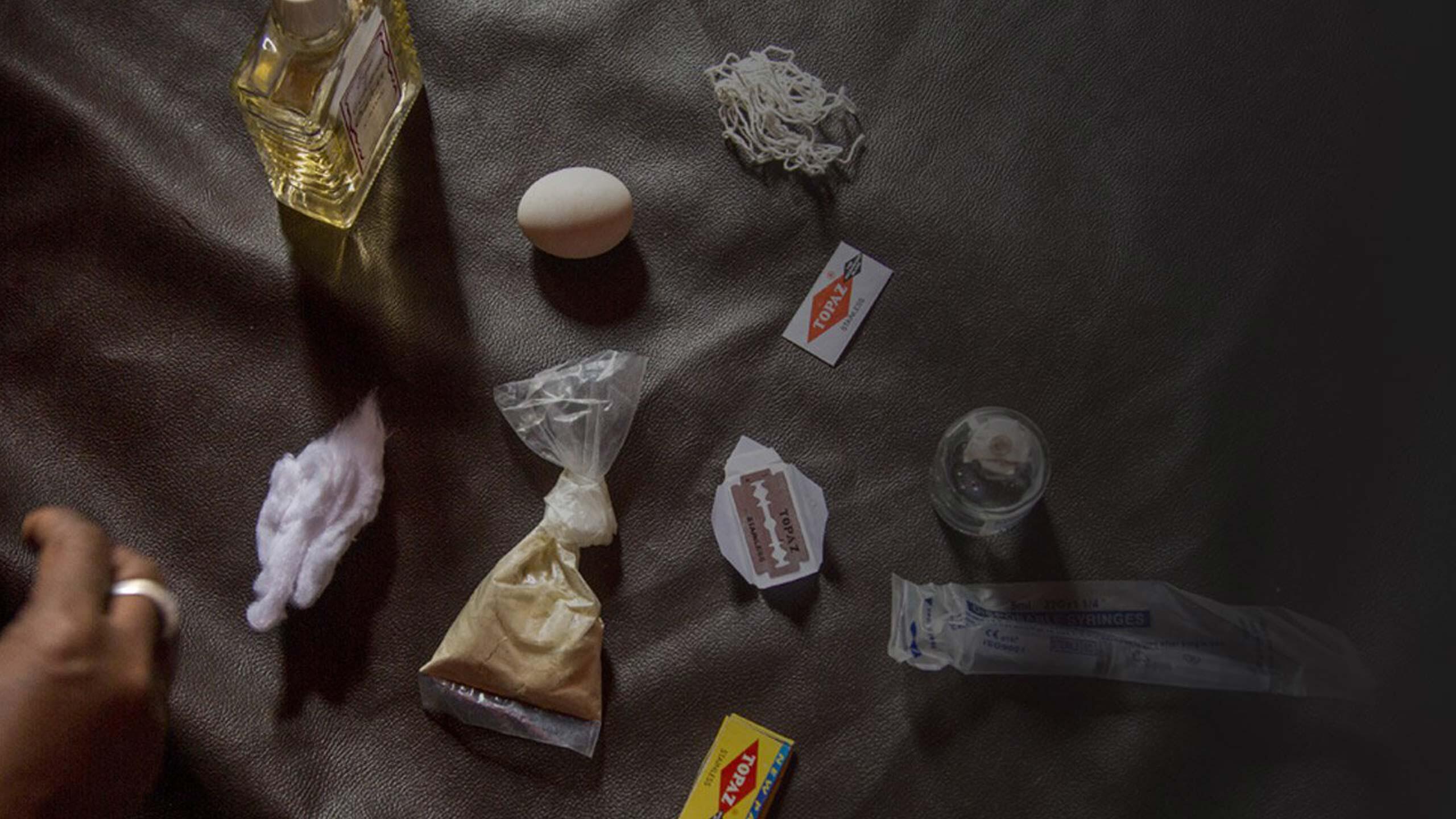

Ms. Ibrahim tries to prevent these problems.

She uses a new razor for every girl she cuts, and she treats their wounds with a powder she creates out of traditional herbs and antibiotic capsules.

© UNFPA/Georgina Goodwin

She gets many of her supplies from local pharmacies.

Her other tools include lidocaine, disposable syringes and cotton wool. She says she pours raw egg onto the wound to promotes healing, then uses a thick thread to sew the girls closed. Afterward, she cleans up with methylated spirits.

© UNFPA/Georgina Goodwin

Though she knows FGM is risky, Ms. Ibrahim denies it has serious consequences like childbirth complications.

Her granddaughter is due to be cut this season, but the procedure has been delayed because the girl has been ill.

© UNFPA/Georgina Goodwin

But Cibaado Ismail knows all too well the risks are real.

Her daughter died in childbirth at age 17; the baby died as well. Ms. Ismail blames FGM. “I have since banned all my 10 female grandchildren from being cut,” she said.

© UNFPA/Georgina Goodwin

At the Hargeisa Institute of Health Sciences, Asha Ali Suldan teaches midwifery students to discourage FGM.

The school – as well as local organizations, religious leaders and youth – have partnered with UNFPA to encourage community members and policymakers to abandon the practice.

© UNFPA/Georgina Goodwin

Ms. Suldan teaches her students how to manage FGM-related complications during childbirth, including how to cut open women who have been sewn shut.

The institute’s midwifery curriculum was recently revised, with help from UNFPA, to cover the wide range of problems that can occur due to FGM.

© UNFPA/Georgina Goodwin

Religious leaders are also working to end the practice.

Sheikh Almis Yahye Ibrahim preaches about the harms of FGM to roughly 5,000 people at his mosque. He is one of six sheikhs in the Arab region who have formed a network calling for FGM’s abandonment.

© UNFPA/Georgina Goodwin

But the biggest difference will be seen among the country’s youth.

In Hargeisa, youth activists with the group Y-Peer talk to health workers, community members and other young people about ending FGM. “I wouldn’t marry any girl who has undergone FGM because I don’t want to live with the health complications,” said Mustafa, one of the youth activists.

© UNFPA/Georgina Goodwin